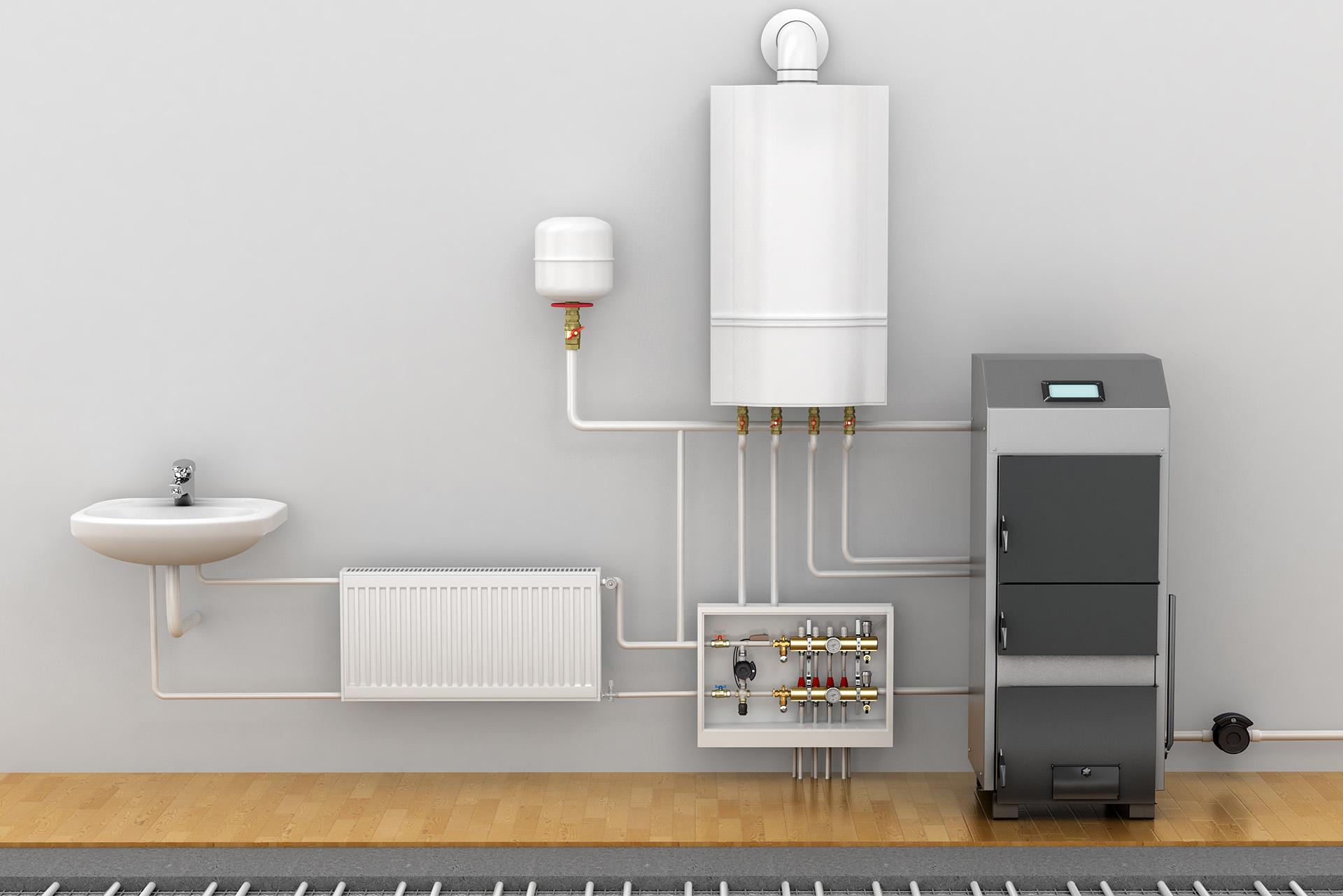

It's August, the month that many Romanians dedicate to renovations. Often this stage also involves changing the central heating system. Therefore, in this article we talk about a new European trend, born from the need to reduce consumption and energy independence: the replacement of individual heating systems using gas or other conventional fuels with other heating systems, such as heat pumps and electric 100%, as well as connection to the heating systems of cities or buildings. The technologies needed to decarbonize heating are now available, with proven performance, but at the same time they are costly for a large part of the EU population.

EU. GAS HEATING PREDOMINATES

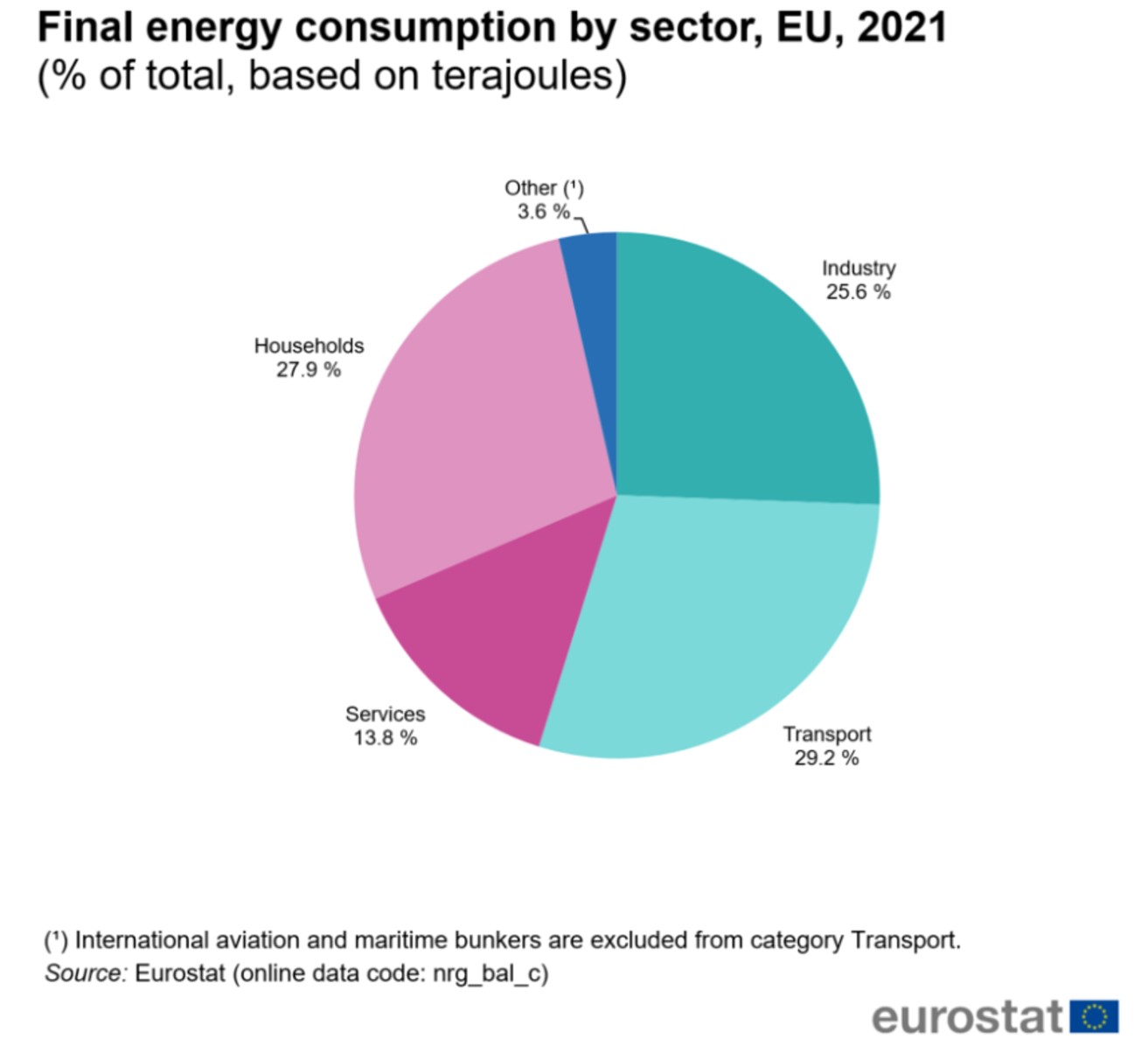

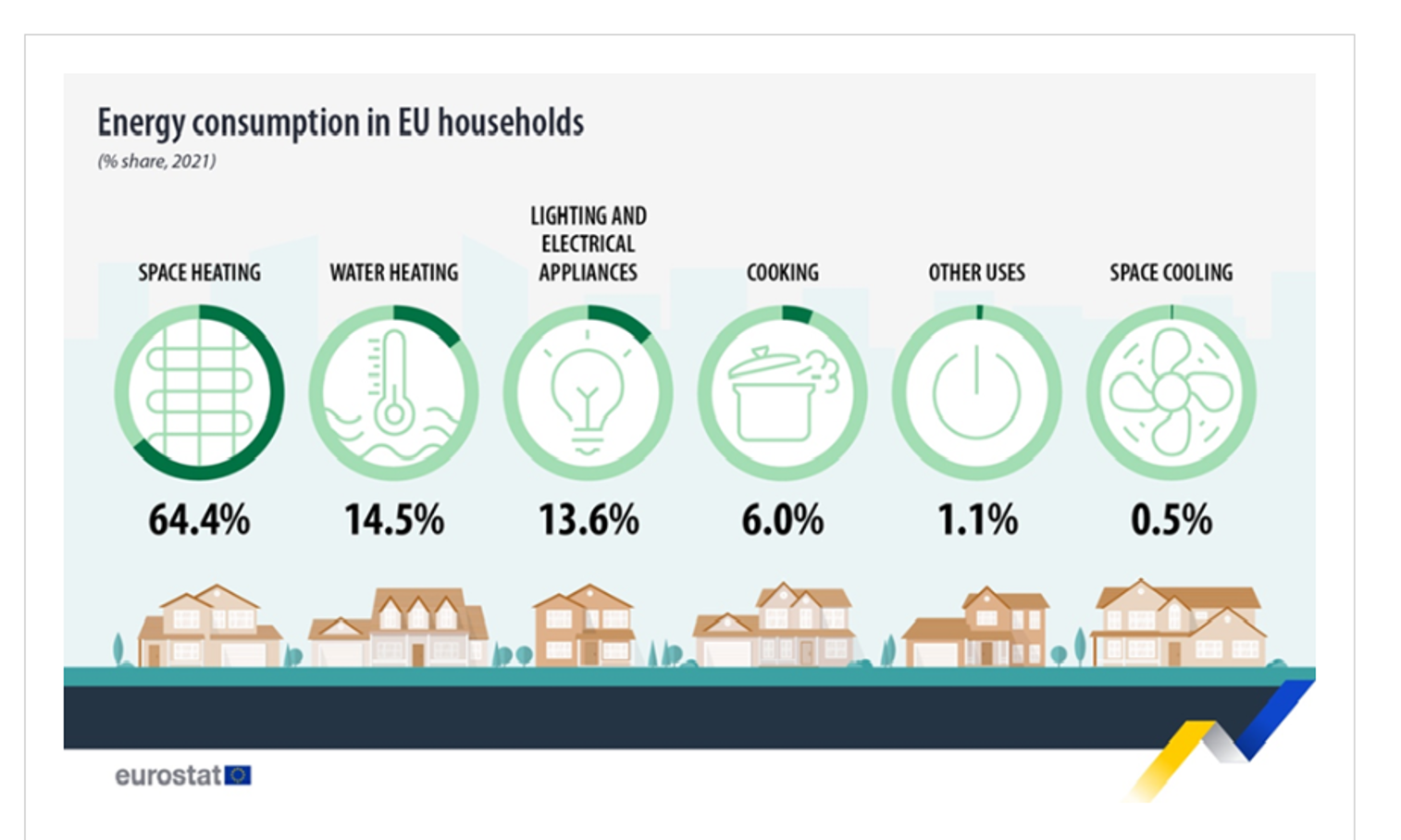

The energy consumption of buildings accounts for 40% of the EU's total energy consumption (residential plus services) and accounts for 36% of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions.

According to EUROSTAT, most of the energy demand in buildings was used for space and water heating, with significant CO₂ emissions. The IEA calculated that in 2022, households emitted about 2400 Mt of direct CO₂ and 1700 Mt of indirect CO₂ emissions through heating processes. Although low-carbon technologies continue to grow, fossil fuels still meet more than 60% of heating energy demand.

The European Commission has proposed to extend the ETS Directive by Directive 959/2023to include fossil fuels used in buildings. The Commission announced a further extension of emissions trading, which could include emissions from the buildings and road transport sectors. "To set the necessary implementation framework and provide a reasonable timeframe for reaching the 2030 target, emissions trading in the buildings, road transport and other sectors should start in 2025.

In the first years, regulated entities should be required to hold a greenhouse gas emissions permit and report emissions for the years 2024-2026. Allowance issuance and compliance obligations for those entities should apply from 2027. This phasing would allow for an orderly and efficient start of emissions trading in buildings, road transport and other sectors. It would also allow measures to be put in place to ensure a socially equitable introduction of the Emissions Trading Scheme in the buildings, road transport and other sectors, so as to mitigate the impact of carbon pricing on vulnerable households and vulnerable transport users.".

It also points out that the number of vulnerable people in the EU is high:

"Some 34 million EU citizens, almost 6.9 % of the Union's population, said they could not afford to heat their homes sufficiently in a 2021 Union-wide survey."

By introducing buildings into the Emissions Trading Scheme, the aim is to increase the number of efficient heating systems, which will most likely lead to an incentive to replace natural gas and conventional fuel plants.

IMPEDIMENTS TO PLANT REPLACEMENT AT EU LEVEL

Of course, those who are currently in the situation of installing or changing their home heating system ask the question: which is more convenient? A heat pump or a gas central heating system? To answer this question, several things need to be considered factories, which vary from country to country and even from building to building:

- specific to each building;

- the level of government subsidies and taxes;

- volatile electricity and fuel prices.

In general, experts believe that a heat pump costs more to install, while offering savings during the running period.

Even if the technical specifics point to an optimistic future for the replacement of gas-fired power plants, however, it is hard to believe that this change can be done quickly, given the very high number of existing plants in the EU, approx. 86 million residential and high upfront costs, making them unaffordable for low-income households.

There are also a number of hurdles related to the actual production and supply of heat pumps:

- The EU is highly dependent on imported compressors and semiconductors.

- lack of qualified installers and service technicians needed to assess the type of installation and its feasibility.

- a technical impediment: fluorinated gases (also known as F-gases), which have a strong greenhouse effect, are used as refrigerants and need to be replaced to avoid additional direct emissions.

Although there is no EU-wide legislation, several EU member countries have started to take action on the use of gas-fired power plants. The Intelligent Energy summarized of such initiatives:

1. Denmark - has banned the connection of new buildings to the natural gas grid since 2013. By 2028, half of all buildings must be connected to the central heating network

2. Norway - has banned the connection of new buildings to the natural gas grid since 2017.

3. The Netherlands - has banned the connection of new buildings to the natural gas grid since 2018.

4. France - by introducing CO₂ emission limits for heating installations in new buildings, de facto banned from 2022 the installation of gas and oil-fired power plants

5. Austria - from 2024, a ban on the repair of old and the installation of new thermal power plants

6. Germany - from 2024 requires 64% of the energy used for new heating systems to come from renewable energy, defacto bans from 2022 the installation of gas and oil-fired power plants

7. Belgium - bans the installation of fossil fuel power plants in new buildings from 2025.

However, because the expansion of emission allowances will have a major social impact, the EU has also put in place a mechanism for a just energy transition: Social Climate Fund, which aims to finance vulnerable households and support investments and initiatives to reduce emissions in the buildings and transport sectors, with the aim of reducing costs for vulnerable households, micro-enterprises and transport beneficiaries.

The Social Climate Fund would be financed from the EU budget, using an amount equivalent to 25% of the proceeds from the trading of emission allowances for buildings and road transport. It will provide €72.2 billion in funding for Member States over the period 2025-2032.

ROMANIA, REPLACING POWER PLANTS AT ITS OWN PACE

In Romania, citizens have asked questions about the EU's objectives and how our country will implement them. However, the relevant ministries have not formulated clear answers. In early 2022, the then Minister of the Environment, Mr. Tánczos Barna, said that individual apartment heating systems would be banned gradually, "not overnight", in new apartment blocks, with no interventions on already installed individual heating systems being considered. He said that there would be a draft law to ban the installation of individual central heating systems in blocks of flats being built, without giving a timetable for the actual legislation.

And the new Environment Minister, Mr. Mircea Fechet, confirmed the need to eliminate individual gas-fired power plants, but also without outlining an actual plan for implementation: "We have not yet made a decision on when these plants will disappear, but in the long term I am convinced that in Romania and in the big urban agglomerations we will have fewer and fewer such plants."

Former Energy Minister, Mr. Virgil Popescu, emphasized the need for newer, more efficient central heating systems, a principle supported by the Government through the Rabla program for household appliances, which also provided incentives for the replacement of apartment heating systems.

According to the Ministry of Energy, cited by hotnews.ro, Romania currently has a total of about 8.5 million homes, of which about 7.5 million are inhabited. Only 1.2 million are connected to centralized systems. One third of Romania's households (almost 2.5 million) heat directly with natural gas, using central heating systems, but also extremely inefficient stoves (at least 250,000 households). About 3.5 million households (mostly in rural areas) use solid fuel - wood, coal - burned in very low efficiency stoves. The rest are heated with liquid fuels (fuel oil, diesel or LPG) or electricity. More than half of all homes in Romania are partially heated in winter.

Romania is currently facing the thorny problem of energy poverty and the Romanians' lack of financial power to ensure the most efficient heating possible. The EU does not impose a timetable for phasing out conventional-fuel power stations and each country sets its own energy and emission reduction strategies. This is why we hope that Romania will take advantage of its rich natural gas resources to ensure that its citizens have access to heating. In other words, we hope that Romania will carry out the transition at a pace appropriate to its population, protecting the vulnerable and making maximum use of its strengths, such as its as yet unexploited deposits and infrastructure with high potential for expansion.